Bond order

Bond order is the number of chemical bonds between a pair of atoms. For example, in diatomic nitrogen N≡N the bond order is 3, while in acetylene H−C≡C−H the bond order between the two carbon atoms is also 3, and the C−H bond order is 1. Bond order gives an indication to the stability of a bond. In a more advanced context, bond order needs not be an integer. A good example of this is bonds between carbon in the molecule benzene, where the delocalized molecular orbitals contain 3 pi electrons over six carbons essentially yielding half a pi bond, together with the sigma bond, the bond order is 1.5. Furthermore, bond orders of 1.0, for example, can arise under complex scenarios and essentially refer to bond strength relative to bonds with order 1.

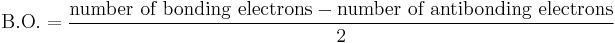

In molecular orbital theory, bond order is also defined as the difference, divided by two, between the number of bonding electrons and the number of antibonding electrons as per the equation below. This often but not always yields the same result. Bond order is also an index of bond strength and is also used extensively in valence bond theory.

Bond orders of one-half can be stable, as shown by the stability of H2+ (bond length 106 pm, bond energy 269 kJ/mol) and He2+ (bond length 108 pm, bond energy 251 kJ/mol).[1]

The bond order concept is used in molecular dynamics and bond order potentials. The magnitude of the bond order is associated with the bond length. According to Linus Pauling in 1947, the bond order is experimentally described by:

where  is the single bond length,

is the single bond length,  is the bond length experimentally measured, and b is a constant, depending on the atoms. Pauling suggested a value of 0.353 Å for b. The above definition of bond order is somewhat ad hoc and only easy to apply for diatomic molecules. A standard quantum mechanical definition for bond order has been debated for a long time.[2]

is the bond length experimentally measured, and b is a constant, depending on the atoms. Pauling suggested a value of 0.353 Å for b. The above definition of bond order is somewhat ad hoc and only easy to apply for diatomic molecules. A standard quantum mechanical definition for bond order has been debated for a long time.[2]

References

- ^ Bruce Averill and Patricia Eldredge, Chemistry: Principles, Patterns, and Applications (Pearson/Prentice Hall, 2007), 409.

- ^ IUPAC Gold Book bond order - PDF

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

![s_{ij} = \exp{\left[ \frac{d_{1} - d_{ij}}{b} \right]}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/8a520d7921809ecc4e5ad5fa69b00fc5.png)